Historical Revisionism as Political Capital

by Manasvini Naren

6 min read • September 30, 2025

Colonialism is not about geographical and political control only; it is a systematic and systemic intervention through which the knowledge systems and culture of the colonized are mauled, deformed, twisted, transformed, and destroyed.

Kundan Singh and Krishna Maheshwari wrote as a prelude to their analysis of James Mill’s History of British India. Mill’s text is a form of social colonialism which perverted the historiography of India through periodization and brought him into the good graces of the then-colonizers of India—the East India Company—of which he became a board member and advocated for the authoritarian rule of India.

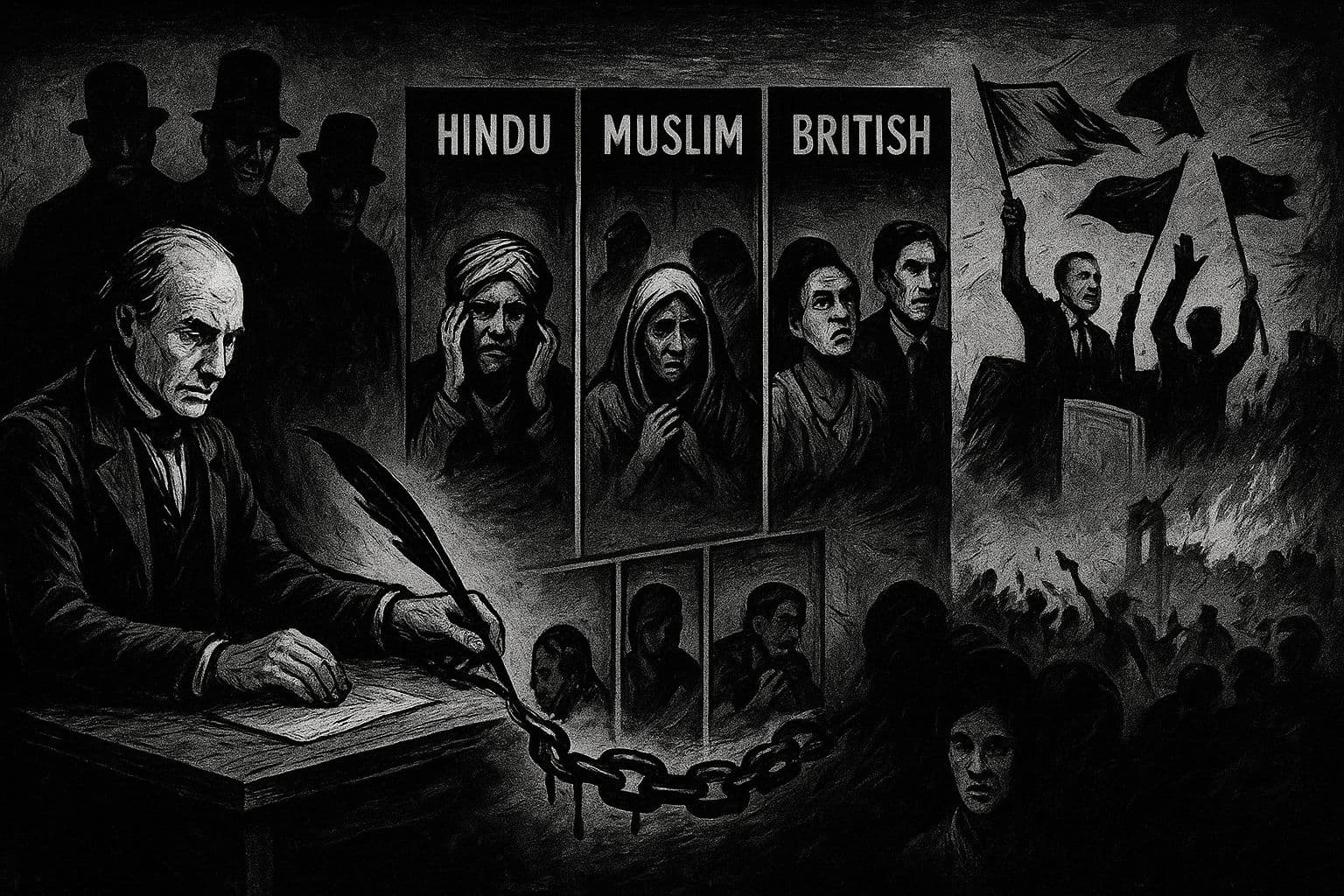

Mill’s work periodized India into three main periods: the ancient, medieval, and modern periods, which correspond to a ‘Hindu’ period, ‘Muslim’ period, and finally ‘British’ India, respectively. This historiography of India is still the long-standing understanding of Indian history. Despite Mill never having set foot in the sub-continent, he was smugly confident about his assessment and interpretation of both Hindu and Muslim practices as barbaric and backward, portraying Britain as the civilizer of India. The idea of civilizing a colony was the main social tool for justifying colonialism. Cultural and social capital played an equally large role in colonialism as physical capital (land, human capital, and physical violence). Cultural and social capital manifested in the form of legislature, governance, racial biology, theology, and the burgeoning Western field of history (of which Mill was a participant), which accumulated in the hands of the oppressors.

Divide and Rule

Britain’s main colonial policy was to ‘divide and rule.’ Britain implemented this policy by pitting princely states against each other, backing one over the other and offering their support with weaponry. Another major play in their ‘divide and rule’ policy was the division of Bengal where they carried out the geographical relocation of millions of Hindus and Muslims, essentially pitting them against each other. However, this oversimplification as we commonly understand it as overlooks the cultural and social tools used to foster a psychological division amongst people. The communalism of pre- and post-colonial India is vastly different owing only to the physical violence by the British but social reimaginations of other religions in the country that fostered communal divisions. Historiography, more specifically, James Mill’s History of British India became the keystone of reimagining and perverting both Hinduism and Islam.

Westernization

The current version of India politics as a liberal state is one of the European imaginations. The earliest era of the Indian National Congress sought to advocate for India through an adoption of European practices. While the later and more radical leaders of the INC rejected this in order to maintain their ‘Indian’ identity, many of the leaders had already undergone the process of westernization. They spoke English, had studied under the British’ curriculum in schools, and were practitioners of western jobs that were only conceived of in India due to colonialism. The Indian bourgeoisie, even while advocating for a free India, were already members of the new, westernized, India.

Aime Cesare, one of the pioneers of post-colonial discourse, believed that even in countries where independence had been achieved, colonialism has so thoroughly perverted their self-image that it was nearly impossible to conceive of a pre-colonial and pre-capitalist vision of their own state.

Mill’s History of British India had homogenized the history of an entire sub-continent and even in a post-colonial India, its influence is preeminent.

Using History in Modern Indian Politics

Romila Thapar writes in The Penguin History of Early India:

Mill, writing his History of British India in the early nineteenth century was the first to periodize Indian history. His division of the Indian past into the Hindu civilization, Muslim civilization and British period has been so deeply embedded into the consciousness of those studying India that it prevails to this day. It is at the root of the ideologies of current religious nationalisms and therefore still plays a role in the politics of South Asia. It has resulted in the distorting of Indian history and has frequently thwarted the search for causes of historical change other than those linked to a superficial assessment of religion.

She underscores the distortion of religion as the lasting result of Mill’s works and was used to advance their own ideologies. The main purpose of Mill’s writings as a utilitarian was to advocate for British rule in India in order to “enlighten” Indian society, thereby corrupting the indigenous aspects of its culture such as Hinduism and Islam.

Bhagat Singh, as he wrote in the document To Young Political Workers, believed that the movement towards Indian independence was an alliance between the Indian bourgeoisie and the British, where one oppressor—the Indian bourgeoisie—was replacing the other—the British colonizers. Considering this and the historical narratives used by the current ruling class of the country, the parallels between distorting another’s religion and creating an out-group as the British did is clearly visible.

Similar to Mill’s historical narrative, the far-right ideology of Hindutva relies on distorting and creating a perceived enemy out of Muslims. Aspects like historical revisionism and creating communal divisions are taken directly out of the playbook of social colonialism implemented by the British in the sub-continent. More attention is paid to the misgivings of our surrounding Islamic neighbours simply for being Muslim than to the institutions and systems left behind by the British that continue to exploit minorities within the country as the British did with India because the ruling class seek to gain from it. Additionally, the mischaracterization of Islam maintained by Hindutva is a direct result of Mill’s misunderstandings of Indian history. Mill’s trilateral division of Indian history beginning with the Hindu period also creates the misconstruction of Hindu’s being the only indigenous religion to the land rather than having significant overlap with Islam. This notion aligns with Hindutva’s desire to create a Hindu ethnostate and ‘return’ to its Hindu roots.

Conclusion

In investigating the political landscape of post-colonial India, apart from the physical separation from the British’ colonialism, there has hardly been a dismantling of the institutions that once upheld colonialism across various fields. With history particularly, Mill’s revisionism was a valuable part of Britain’s social colonialism of India. However, the continuing perpetuation of distorted history for the social oppression by the bourgeoisie underscores the lingering spectre of British colonialism in India. Further, it reveals how it is beneficial for the ruling classes to follow in colonial footsteps rather than practice decoloniality if they are to maintain their position in the hierarchy of Indian society.

About the Author

Manasvini Naren is a student of History and Political Science at Trinity College Dublin. Her research interests lie in colonization and its continuing effects on the Global South and post-colonial nations. She is also interested in grassroots politics like direct action, campaigning, and protests.