SIR in Bihar: Nail in the Coffin, or Tip of the Iceberg?

by Pakhi Dhokariya

6 min read • September 26, 2025

Human memory is fleeting. In trying to recall one account, we often forget another. Amidst this forgetting, debates around the Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of electoral rolls in Bihar have managed to enter mainstream political discourse. As citizens grapple with the peculiarities of SIR, the critical question emerges: is this simply a reappraisal of rolls to make the electoral process more credible, efficient, and updated, or does it reveal deeper structural concerns that merit scrutiny?

What exactly is SIR?

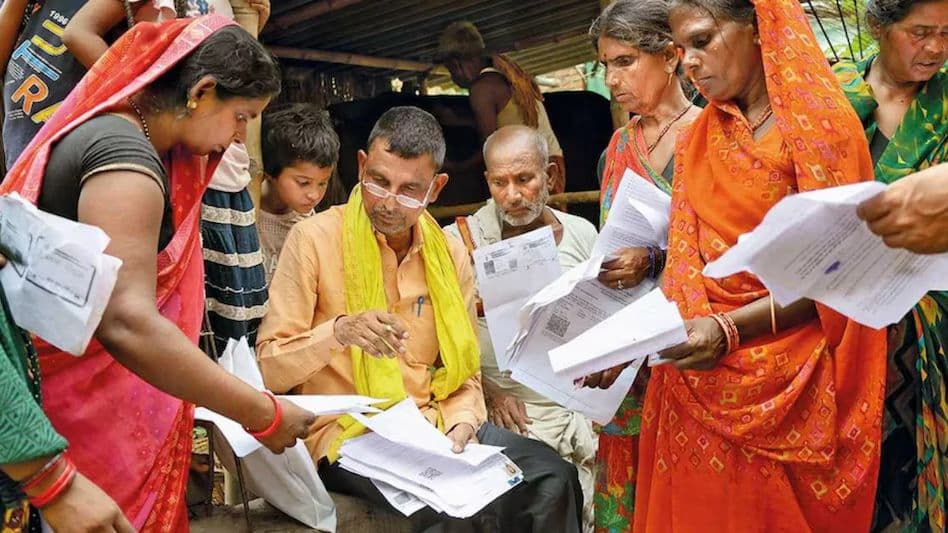

The Special Intensive Review (SIR) refers to the revision of electoral rolls undertaken by the Election Commission of India (ECI) to curb ghost entries and rectify voter miscalculations, as Bihar gears up for assembly elections later this year. The revision process began on 25 June 2025 and is scheduled to conclude on 30 September 2025, with the publication of final rolls soon after. The last SIR in Bihar was conducted in 2003.

Its constitutional grounding lies in Articles 324 and 326 of the Indian Constitution. Article 324 vests the "superintendence, direction and control" of elections in the ECI, while Article 326 establishes adult suffrage as the basis for elections. Supplementing these, Section 15 of the Representation of the People Act, 1950 mandates the preparation of electoral rolls under the ECI’s authority.

To verify entries, the ECI has listed 11 acceptable documents, including a birth certificate, passport, matriculation certificate, and permanent residence proof issued by a state authority. Following a recent Supreme Court ruling, Aadhaar has also been included as a valid document.

The Debate Over SIR

The SIR process in Bihar has sparked fierce arguments from multiple directions. Critically, the controversy unfolds across three layers:

1. Timing and Political Strategy:

Opposition parties argue that conducting SIR just before assembly elections is an attempt to give the ruling NDA a political edge by subtly influencing voter rolls and potentially stifling unfavourable votes. Citing previous instances like Maharashtra, critics allege that ‘vote chori’ or ‘vote theft’ could be facilitated through this exercise. They contend that the timing itself feels strategic, particularly with only a few months left before Bihar votes and millions of names at stake. In response, the Election Commission maintains that procedural safeguards have been put in place: all citizens and political parties have a month-long window to submit claims and objections prior to final publication of the rolls. A two-stage appeal process exists, first with the district magistrate, then with the Chief Electoral Officer. The EC insists the revision is proceeding smoothly and on schedule while the Supreme Court of India assures that any confirmed illegality could result in the process being scrapped.

2. Rights, Safeguards, and Process:

Proponents of SIR argue that the exercise helps address inclusion errors by detecting illegal migrants, removing deceased voters, and correcting inaccuracies that have been amplified by rapid migration and urbanisation. Critics, however, warn that the process risks large-scale disenfranchisement. With projections suggesting that more than 65 lakh entries could be deleted, the effort to eliminate ghost voters may come at the cost of widespread exclusion. More significantly, the burden of proof shifts from the state or the objector to the citizen, placing a disproportionate strain on the poor, vulnerable and resource-constrained. This crucially departs from earlier understanding of the state’s role when the responsibility of proof was primarily held by the state or the objector.

3. Trust in Institutions and Methodology:

Underlying the immediate disputes is a deeper ‘crisis of trust’ in the Election Commission as an independent institution. Critics point to an accelerated timeline, logistical gaps and reports that Block Level Officers were not sufficiently trained or did not visit many villages. Many argue the methodology risks excluding the most vulnerable, especially marginalised communities and women. The implementation has triggered protests and legal challenges, with the Supreme Court now actively examining whether the revision is arbitrary, opaque, and unconstitutional.

Citizenship and Universal Franchise

These concerns extend beyond technicalities and speak to the foundations of citizenship itself, especially the idea of universal adult franchise. Any failure to submit the requisite documents risks deletion from rolls, creating a paradigm in which exclusion is procedurally normalised.

During the freedom struggle and the framing of the Constitution, leaders consciously envisioned citizenship as inclusive and encompassing, even in the shadow of Partition. The burden of verification rested on the state, not individuals. Yet, as political scientist Yogendra Yadav warns, “SIR represents a tectonic shift in the architecture of universal adult franchise.” Questions loom over ECI’s credibility and authority in shaping criteria for citizenship. This politically ingenious move holds the potential to shake the very discourse on citizenship. Whether the principles of citizenship are exclusionary at core is a question to look forward to.

The Larger Structural Malaise

Here lies the central question: is the debate about SIR merely Bihar-specific, or is it symptomatic of a broader structural reality, where exclusion is being normalised in the name of efficiency?

Efficiency, speed, and accuracy have become the holy trinity of governance.

Ghost entries must be deleted.

Services must be digitised.

Welfare must be Aadhaar-linked.

But what happens when efficiency comes at the cost of inclusion? The pattern is not unique to elections. In welfare delivery too, Aadhaar-linked systems regularly deny benefits to those unable to access the digital ecosystem. French philosopher Michel Foucault once wrote that modern regimes don’t rule through brute force, but by coaxing individuals to discipline themselves. India’s governance, too, seems to be shifting in that direction: the state shrinks its responsibility, while the citizen shoulders the blame.

Fail to get rations? Your fingerprint didn’t match.

Fail to vote? You didn’t produce the right papers.

It sounds technical, even neutral. But the effect is deeply political: a gradual depoliticisation of citizenship itself. Structural questions of inclusion are drowned out by bureaucratic processes of verification.

The Real Choice Before Us

It’s tempting to see SIR as just Bihar’s problem. It’s not. This is not about one revision of one state’s rolls, but about the direction of our democracy: do we value efficiency more than inclusion? Do we see citizenship as a universal guarantee, or a conditional one, always up for question, always needing proof?

Noise and distraction will abound. But at its heart, the real issue is stark: SIR is not only a nail in the coffin of inflated rolls. It may also be the tip of an iceberg, beneath which lies a larger shift in how citizenship itself is defined in India.

About the Author

Pakhi is a final year student of Political Science and Economics at Lady Shriram College for Women. With a strong interest in research, she is passionate about exploring the fields of Comparative Politics, Political Economy, and Digital Political Communication. She seeks to bridge institutional theory, political culture, and the evolving dynamics of the digital public sphere. Her academic journey is shaped by an inquiry into how power, technology, and governance intersect in contemporary democracies.